In a Conversation With Marton Perlaki On The Context Of Signifiers

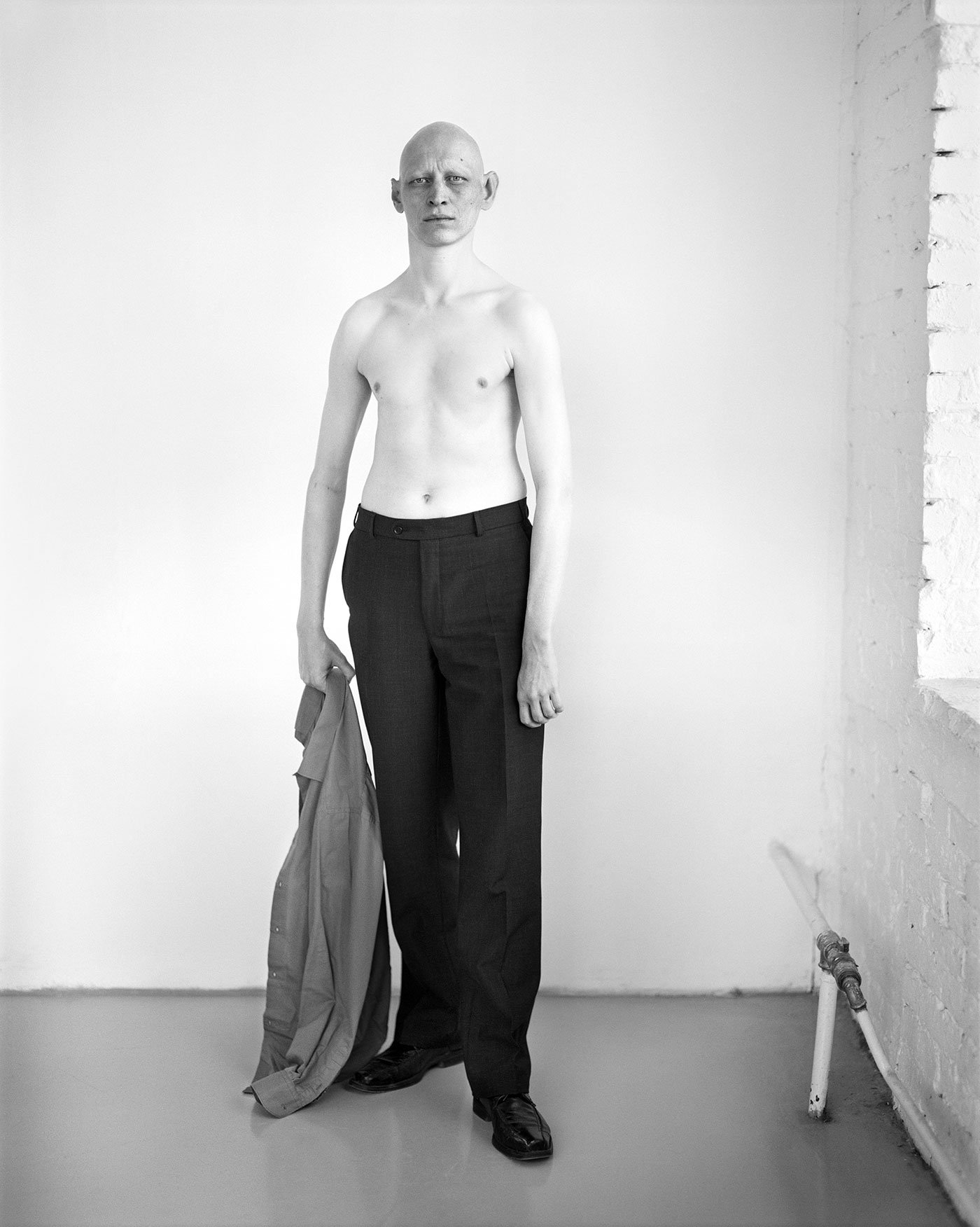

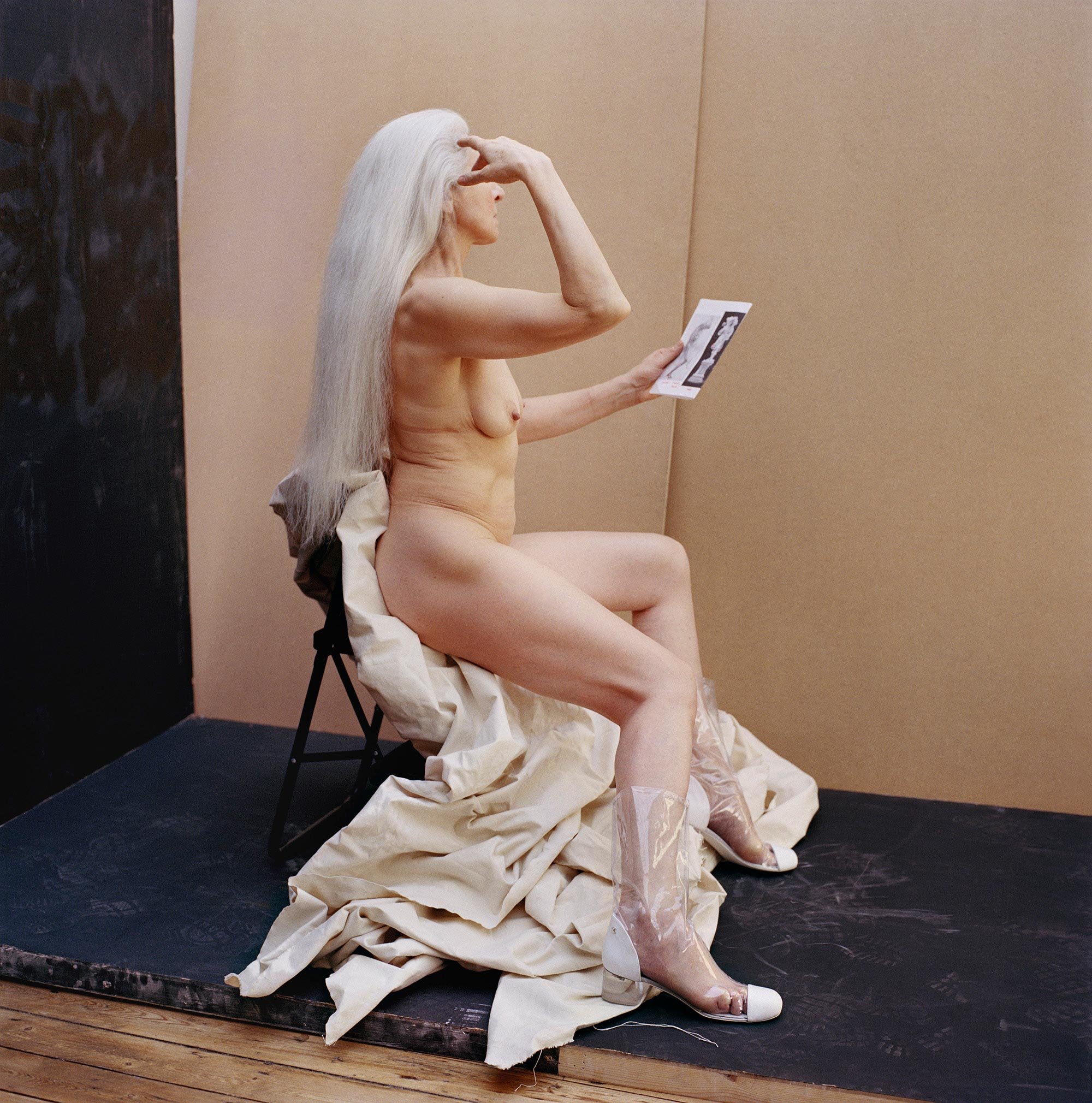

Marton Perlaki, a Hungarian photographer who currently lives and works in London. He is constantly attempting to explore layers of meaning while relying on personal interpretation and technical knowledge, Marton empowers the colors to convey feelings and purpose.

Working with the understanding of what an object could stand for and the various possibilities to approach the deeper context is one of the main themes recurring in Marton’s work. Through the emotions that arise from viewing the photographs, we learn about the possible meaning or reasons leading to this realization, first and foremost connected to oneself.

Marton agreed to a Zoom call to discuss his work and the processes which enable him to create. It was the beginning of January, a sunny day in Tel Aviv, about 25 degrees Celsius, quite the opposite of weather in London. As Marton semi-jokingly referred to one of his short-term goals, “I’m thinking of finding a studio with heating. That would be a step up!” We discussed topics such as social media, a metropolis as a stage for creators, and the idea of finding context for the object that is presented. We also spoke about the need for diversity in life and in the creative work, the stimulus to make art, closing the chat with Marton’s favourite cinematographers and film directors.

‘There are times when you feel a little tired from what you do. You need stimulus. Looking for new challenges is really important for me.’

Let’s start with a ‘simple’ question. Today a lot of people engage in photography. Being involved in art became much more approachable, at least via social media. I wanted to hear your take, where does the fine line between photography as an art and photography as a hobby cross? What is the element that separates those two?

If you're mindful and dedicated to what you’re doing, and you're creating good work, you most probably will become a decent photographer or artist. It doesn't necessarily mean you’ll be a good one, but you’ll be one. So, you’re not a hobbyist, you’re not doing it on the sidelines, you’re fully committed. With time, if you’re resilient and focused enough, your name can become its own currency. Social media is a powerful platform and should be used wisely to show one's work. I haven’t yet figured out the most efficient way to make use of it.

What is your drive to create: waking up in the morning, taking your camera, thinking about a new series you want to work on for a long, extended, period of time?

I just can’t imagine myself not doing that. I enjoy what I do. I think that’s the simplest answer. That being said, there are times when you feel a little tired from what you do. You need stimulus. Looking for new challenges is really important for me. I guess this is why I’m spending days experimenting in the darkroom, other days I’m drawing, and I’m also taking photographs. This kind of variability and saturation in my practice is quite important.

‘It’s not a set idea or a set of emotions I want to get out to the world. It works slowly, I discover things throughout the process. At the end of the day, I want to surprise myself with the work. I don't want to illustrate or over-explain things.’

It seems that photography, like other forms of art, can be healing but also painful when an artist goes deep inside himself to understand their feelings or periods in his life and interpret them. I was checking one of your exhibitions last year, Soft Corners, the series about the process of dealing with family tragedy, your father passing away, to research the emotional side. I wanted to ask you about the psychological factor of facing what you have experienced, going back to research it. What does it mean to you to investigate those feelings and create art of it?

When I start working on a series, I’m naturally gravitating towards subject matters. Creating a series takes up a lot of time for me, and it gradually shifts along the way, which I’m trying not to control too much. So, it’s the same when it comes down to something deeply emotional. I have a starting point that I’m interested in, and I’m trying to find a question, working through the process of thinking about the subject matter. It’s not a set idea or a set of emotions I want to get out to the world. It works slowly, I discover things throughout the process. At the end of the day, I want to surprise myself with the work. I don't want to illustrate or over-explain things.

Yes, basically, it's about creating an abstract object instead of showing reality, as what happens with documentary photography. Working with abstract objects is something one can see a lot in your work, presenting what you want to say without actually saying it.

I was never really interested in photo documentary. As we ask photography to capture ‘reality,’ photographers are in a difficult position. The reason why I photograph something is because I have a particular interest in a subject matter. Not necessarily the subject is what interests me, it's more what it could potentially represent. I’m not interested in an ice cube per se. I’m more interested in what an ice cube could stand for. I enjoy thinking about the multiple layers that a mundane object represents or means in a certain context.

‘I learned how to assess a quickly unfolding situation from studying photojournalism. And from cinematography, I learned to plan and the need to be precise technically.’

I think one can notice that you have layers in your work, in which you tend to present objects abstractly. So, the layers are filled with a subconscious material, perhaps coming as your interpretation of this object. Trying to play with the viewer suggesting they also interpret it in their way, thus creating even another layer.

Yes, an object is not just an object. It always has a context.

You mentioned photojournalism, and documentary photography, saying you’re not really interested in that. You studied this topic and also, you studied cinematography, such a different sphere of creation. What did you enjoy, and how do you see those spheres affecting your work? As, probably, there’s a slight combination of those two genres in your thought processes, which lead to the final image.

What I really enjoyed while studying cinema and studying photojournalism is that I had a chance to expose myself to these exciting worlds of image-making. I made the decision not to follow these roads. I have huge respect for photojournalists and cinematographers, but I don’t think I’m quite the right fit for any of these professions. But I learned a lot. I learned how to assess a quickly unfolding situation from studying photojournalism. And from cinematography, I learned to plan and the need to be precise technically.

‘As a photographer (working mostly with an analogue camera and techniques), you need access to the infrastructure that usually only a large city can provide. It’s also good to be able to meet like-minded people to learn from and collaborate with.’

It is a combination of research, technicality, and different approaches you learned. I was wondering about you as an artist living in several capitals: in Budapest, London, New York, and your experiences. How would you describe your hometown?

That’s a really good question because I rarely had to describe it much before. Budapest, as a city, is a ghost of a prosperous past. It’s also provincial, which is probably my biggest issue with my hometown.

How would you describe the differences between people living in all those capital cities you experienced? What did you enjoy the most about changing the countries you lived in, changing the atmosphere?

Well, of course, the biggest difference, when you live in New York, you have access to an insane amount of inspiring and versatile impulses. As a photographer (working mostly with an analogue camera and techniques), you need access to the infrastructure that usually only a large city can provide. It’s also good to be able to meet like-minded people to learn from and collaborate with. Diversity is probably the most important aspect a metropolis offers.

I would like to close the interview with two last questions: what are your plans for 2021? Currently, it seems we're facing a continuation of 2020.

Yeah, it’s difficult to make solid plans these days. I have many things that I want to do, of course, so let’s see what’ll happen in 2021. Now, I’m thinking of finding a studio with a heating. That would be a big step up! That's for the near future. I want to do at least one show this year, not sure it can happen, though.

Is there a theme or a topic you’re currently exploring?

Yes, but it’s a bit too early to talk about it.

Obviously, we’ll wait for an update on that! I think we touched on a lot of interesting topics. Perhaps, to close the interview, you can name one or two best cinematographers you came across during your studies, who managed to turn your soul upside down (when you think of their creations you feel something until today).

Oh, great cinematographers, there are plenty. One of my favorite cinematographers is Roger Deakins. He has a podcast, which I would recommend if somebody is interested in cinema and the world of cinematography. (The podcast is called Team Deakins). Also, there are many other great cinematographers like Matyas Erdely, who is a fellow Hungarian.

In terms of directors, one who interests me the most at the moment is Ruben Östlund. He's a Swedish director. He directed The Square and Force Majeure. He has a sharp and smart sociological point of view on modern society. I’m into Swedish cinema, so Roy Andersson is also a director whose films I really enjoy. I also did my final thesis on Roy Anderson actually.

Sounds fantastic. I won’t take much of your time. I would like to thank you so much again.

No, thank you!